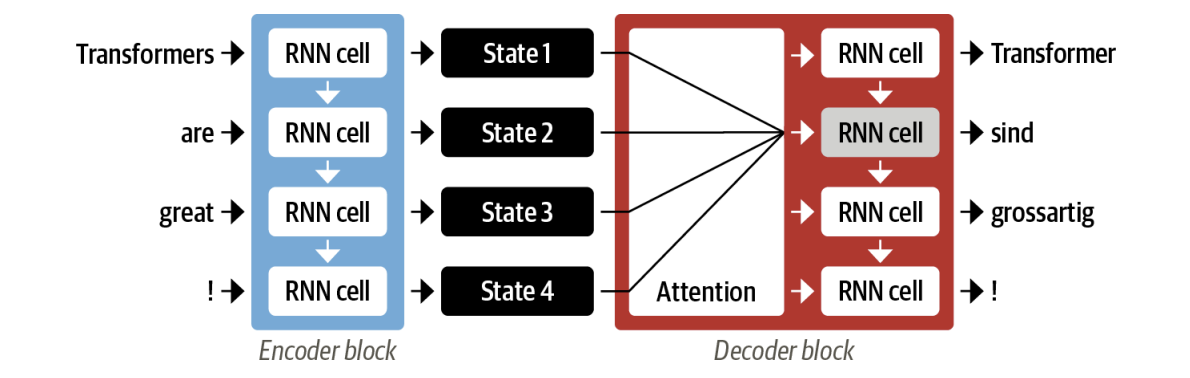

The main idea behind attention is that instead of producing a single hidden state for the input sequence, the encoder outputs a hidden state at each step that the decoder can access.

However, using all the states at the same time would create a huge input for the decoder, so some mechanism is needed to prioritize which states to use.

This is where attention comes in: it lets the decoder assign a different amount of weight, or “attention,” to each of the encoder states at every decoding timestep.

This is where attention comes in: it lets the decoder assign a different amount of weight, or “attention,” to each of the encoder states at every decoding timestep.

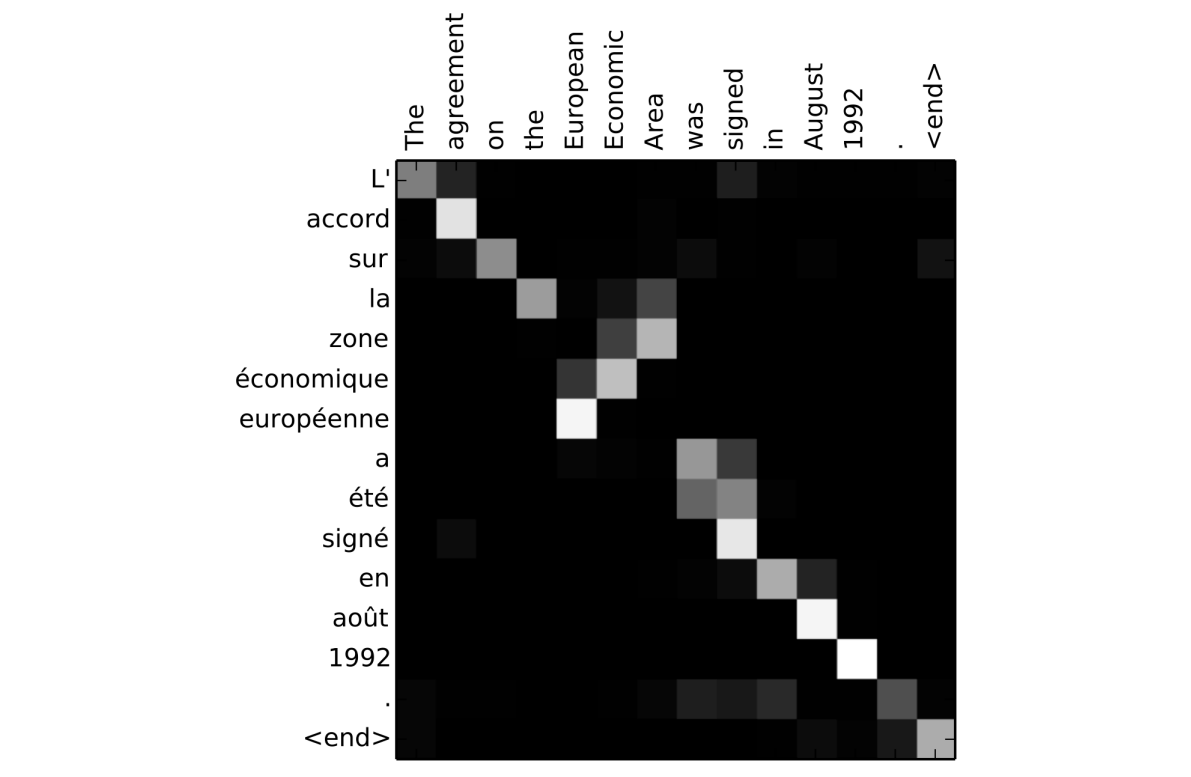

By focusing on which input tokens are most relevant at each timestep, these attention-based models are able to learn nontrivial alignments between the words.

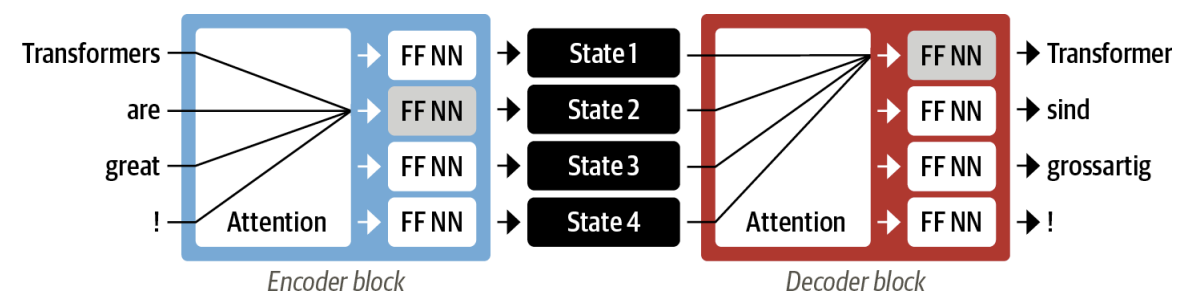

A major shortcoming with using recurrent models for the encoder and decoder: the computations are inherently sequential and cannot be parallelized across the input sequence. With the Transformer, a new modeling paradigm was introduced: dispense with recurrence altogether, and instead rely entirely on a special form of attention called self-attention.

Self-attention

The “self” part of self-attention refers to the fact that the weights are computed for all hidden states in the same set—for example, all the hidden states of the encoder. By contrast, the attention mechanism associated with recurrent models involves computing the relevance of each encoder hidden state to the decoder hidden state at a given decod‐ ing timestep.

The main idea behind self-attention is that instead of using a fixed embedding for each token, we can use the whole sequence to compute a weighted average of each embedding. Another way to formulate this is to say that given a sequence of token embeddings , self-attention produces a sequence of new embeddings where each is a convex combination of all the :

the coefficients are called attention weights and are normalized. The new embeddings is also called contextualized embedding since it (should) incorportate context information.

Scale dot-product attention

Is the most common way to compute attention introduced in the “Attention is all you need” paper.

- Project each token embedding into three vectors called query, key and value.

- Compute attention scores. We determine how much the query and key vectors relate to each other using a similarity function. In this case this function is a scaled dot-product. The output is a attention score matrix.

- Compute attention weights. To limit the size of the dot-product we introduce a normalization of (assumes gaussian variance), and scale the scores with a softmax function to ensure that they are non-negative and add to one. The resulting matrix contains all attention weights .

- Update the token embeddings. We use the value vector:

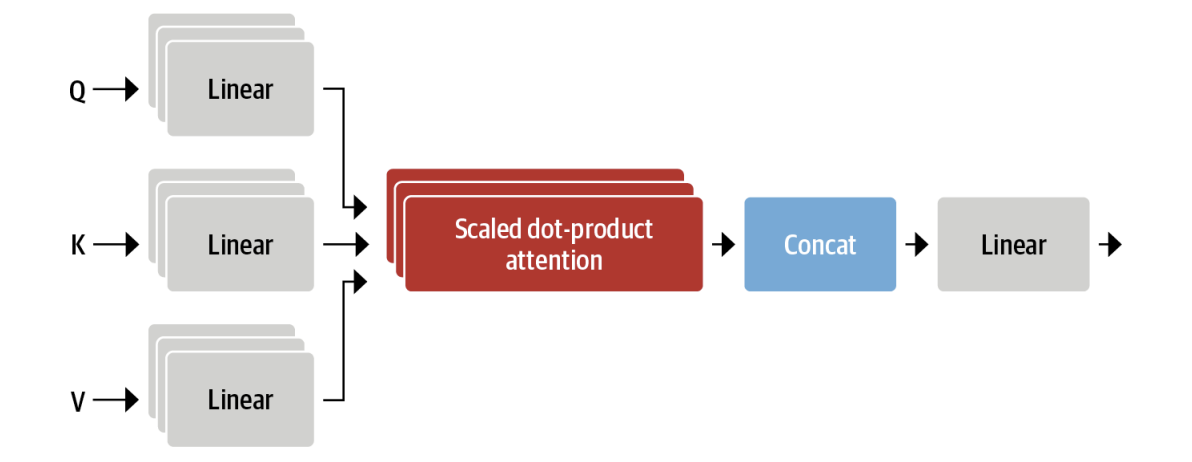

Multi-headed attention

It also turns out to be beneficial to have multiple sets of linear projections, each one representing a so-called attention head. But why do we need more than one attention head?

The reason is that the softmax of one head tends to focus on mostly one aspect of similarity. Having several heads allows the model to focus on several aspects at once. Obviously we don’t handcraft these relations into the model, and they are fully learned from the data.

The reason is that the softmax of one head tends to focus on mostly one aspect of similarity. Having several heads allows the model to focus on several aspects at once. Obviously we don’t handcraft these relations into the model, and they are fully learned from the data.

In practice it is customary to choose the projection dim as smaller then the embedding dimension, for example BERT has 12 attention heads and the dimension of each head is ( is the embedding dim).